Getting to Grips with Classic Books

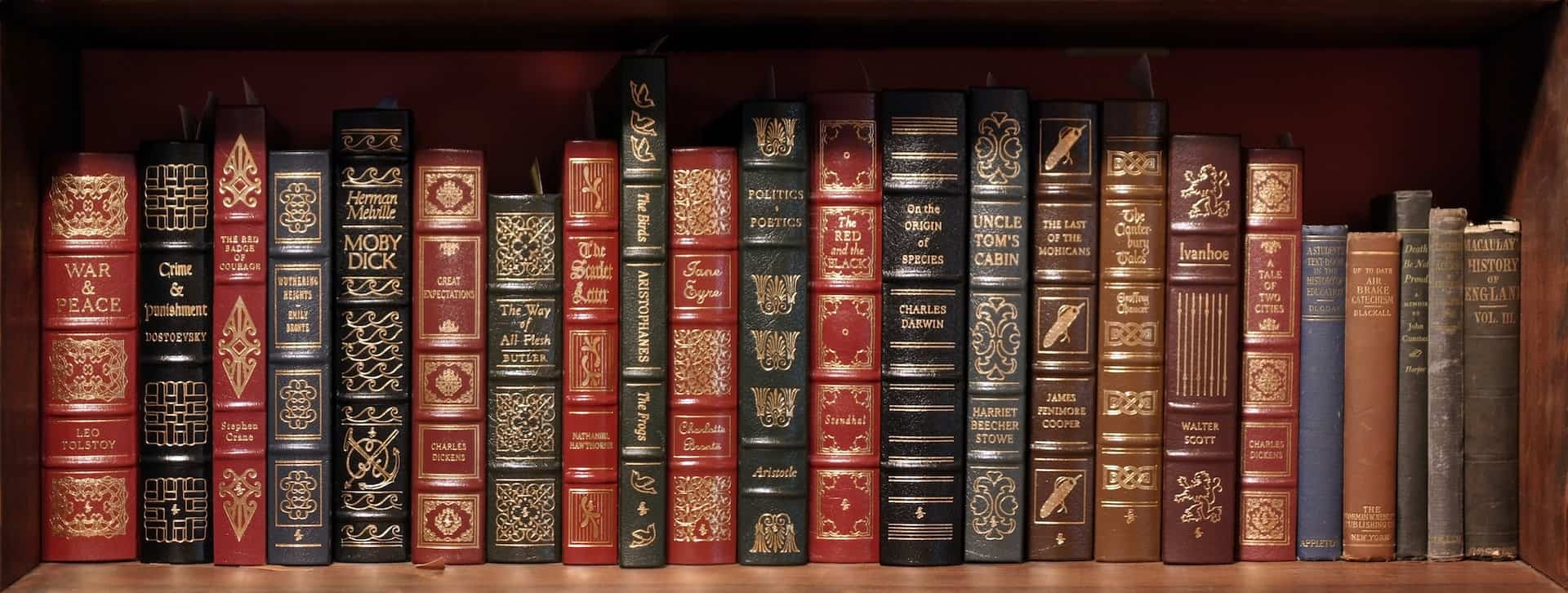

So, you want to try your hand at the classics, eh? Standing in front of a bookcase can be daunting enough — let alone being faced with a civilisation’s entire literary canon.

‘Classic’ books are something we, as readers, seem to get repeatedly stuck on, from elevating them to inaccessible heights to being, if we’re honest, rather close-minded about what exactly we’ll accept as a ‘classic’.

If you want to find out more about where to start with classic books or, indeed, what actually makes a classic, consider this your expert guide.

What is a classic book?

When we speak of ‘the classics’, we are referring to a set of works that have been given particular significance in the cultural imagination owing to their themes, perceived value, teachings, writing style, and social impact.

How does a book become a classic?

Throughout literary history, this question has been asked time and time again — by readers and writers alike. So much so that certain works about what makes a classic have become classics themselves.Take, for example, modernist poet T. S. Eliot’s essays on the meaning of classics and the theoretical analysis of the classics by famous writers such as Ezra Pound. Meta, right?

Generally speaking, however, the processes by which a literary work becomes a classic involves the following four concepts:

- Time

- Criticism

- Context

- Culture

Once in the hands of readers, a book will be read and critically engaged with over time. Readers will apply the themes and content of the story to a variety of different contexts: their lives, current affairs, political matters, global scene, and so on. After a while, the story — in all its variations and adaptations — roots itself within a community’s culture, becoming embedded as a classic to be returned to again and again.

At this stage, it is important to consider the role of the education system on the ‘canonicalisation’ of books (that’s the process by which books are assimilated into the literary canon as a ‘classic’). Once a book is taught as a part of a curriculum, it is safe to say that it has been ‘accepted’ as a work of value or interest by a society. What books did you study at school? In recent years, a few ‘big’ names have been:

- Dracula, Bram Stoker (1897)

- The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde (1890)

- To Kill A Mockingbird, Harper Lee (1960)

- The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood (1985)

- Shakespeare’s plays and Sonnets

- The poems of Carol Anne Duffy

Of course, it’s much more complicated than that. Some books, as we have explored before, have a much more turbulent reception (with some even being banned and tarred with infamy before becoming classics).

Some of the best-loved classics

When you think of a classic book, what springs to mind? For many of us, images of classic nineteenth-century novels will surface. The likes of: Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Pride and Prejudice, Great Expectations, and Mill On The Floss being just a few.

These works have ‘spoken’ to and moved their readers for generations with their vivid images and gripping plots. However, it is important to recognise the limitations of classics. For one, they are usually novels. While we love a novel as much as the next person, this is just one genre of literature — what about plays, poems, and non-fiction? When it comes to modes of expression, long novels with even longer sentences aren’t the only way to write (looking at you, Dickens).

There are certainly different types of classics. Modern American classics, for example, have provided us with hundreds of excellent pieces of drama, poetry, and prose alike. Just a few examples include:

- A Streetcar Named Desire, Tennessee Williams (1944)

- The Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Sallinger (1951)

- The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck (1939)

Going beyond ‘the classics’

While having a collection of treasured, widely-read ‘classics’ has so many benefits, there are also a few problems with regarding books in this way.

One issue is that labels can be exclusive as much as they can be inclusive. When we include certain books under the label of classic, it is worth thinking about the works we are leaving out — deliberately or accidentally.

Another reason is it is often the case that certain types of books are more likely to be regarded as classics than others.

Historically, the literary canon has been dominated by white, upper-class, male authors who have enjoyed greater access to education, freedom of speech, and literature as well as the space and time to write their experiences (a concept well-put by Virginia Woolf’s essay on gender and writing, A Room Of One’s Own).

There is also often an inherent Westernised bias when it comes to what makes a classic. If we’re talking about the UK’s version of classics, it is rare to find works in translation or from non-European countries on the list. As such, many voices get drowned out. Books containing the experiences of ethnic minorities, those from varying socio-economic backgrounds, people with disabilities, women, people of a marginalised gender, and children are much less likely to be regarded as classics.

Here are just a handful of excellent, powerful works only recently accepted as classics that help broaden the ‘classic’ lens:

- The Colour Purple, Alice Walker (1982)

- Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Husrton (1937)

- Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe (1958)

- Oroonoko, Aphra Behn (1688)

- Beloved, Toni Morrison (1987)

- Sister Outsider, Audre Lord (1984)

- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Autobiography (1845)

- Any poems by Phyllis Wheatley (1700s)

The narrow definition of a ‘classic’ is a major oversight on our part as readers. So, now it’s up to us to expand our horizons and give time and attention to all the overlooked works out there.

Read widely

If you’re looking for inspiration for your next read, keep up with our blog, or check out our latest reviews page for a constant stream of reviewed literature hot off the press!