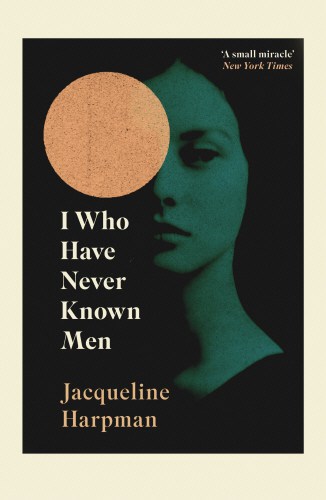

I Who Have Never Known Men

Jaqueline Harpman

Thirty-nine women and one young girl are being held captive in a cage underground, guarded by men who never speak to them. None of these women know why they are prisoners, or why there is a child among them. One day, an alarm sounds. The guards flee. The captives escape. The story that unfolds next is one of immense bewilderment, disorientation, and overwhelming loss.

Harpman’s novel was originally published in 1995 in French as Moi qui n’ai pas connu les hommes, but has since been translated and loved by many more audiences in English since 1997, as an excellent post-apocalyptic work of modern science fiction.

Jacqueline Harpman is a Jewish author whose family fled Belgium when the Nazi regime invaded during the Second World War. During this time, Harpman was just ten years old — a similar age to the only child character in the story. As Harpman grew up, the horrors of the Holocaust were unfolding all around her. This context of persecution, violence, and suffering forms a consistent backdrop to Harpman’s novel in its themes of arbitrary incarceration and dehumanisation.

“Bleak but fascinating”

- The New York Times

In her adult life, Harpman returned to Belgium and became a psychologist, another strong bearing on the direction of the narrative. Taken at face value, the story functions as a deep dive into the tortured psyche of the ever-wandering protagonist as she ages. However, Harpman uses this laser focus to subtly reflect on the nature of human beings as a whole and whether mass attempts to remove humanity can ever truly work.

Harpman leaves us with the inspiring conclusion that humanity is not an accessory but an innate, inbuilt phenomenon that can never fully be stripped away – no matter how hard the powers that be may try.

“This understated dystopian novel from Belgian author Jacqueline Harpman feels destined to become a modern classic”

- Callum McLaughlin

The prose and dialogue are sparse and honest in much the same way as Margaret Atwood’s lines in The Handmaid’s Tale. This comparison has been drawn many times by readers; however, where Atwood’s story becomes an explicitly gendered dialectic mapped onto the power dynamic between victim and oppressor, Harpman’s prose is far more to do with the singular struggle for survival. Less filled with pseudo-feministic moments of rebellion, Harpman’s monotonous narrative appeals to all in its ongoing search for hope and humanity among barren lands.

The first half of the narrative crawls through the passing of time at an agonising pace. The narrative voice logs every minuscule detail and thought, enmeshing the reader — women or not— with the captive women in the cage through a kind of collective consciousness.

Despite the communal experience of suffering, there is something distinctly unique about the narrator. She is a blank canvas with no memory of life before imprisonment. Readers, then, become both unwitting accomplices in her suffering and passive agents in her creation of memory. We follow her as she experiences rage, fear, and — most poignantly — awe at a world which never fully reveals itself to her. Prepare yourself to feel all that and more if you enter Harpman’s bleak, lonely world.

| ISBN | 978-1784877200 |

|---|---|

| Pages | 208 |